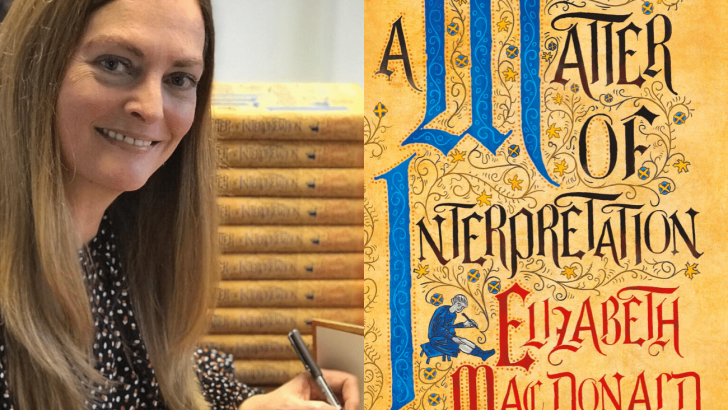

A Matter of Interpretation

by Elizabeth MacDonald (Fairlight Books, £12.99)

Elizabeth MacDonald’s absorbing novel is built up around the character of the celebrated Michael Scot – now known to be of Scottish rather than Irish origin – and his relations with the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Hohenstaufen II and various other players in the Middle Ages, the Church, the Arabs, the Jews and the plotting and conniving that was all so important an aspect of ecclesiastical and academic life (almost indistinguishable then) in those centuries.

Elizabeth MacDonald is a Dubliner who now lives with her family in Pisa, after studying and teaching in different parts of Italy. She has translated many Irish authors’ works into Italian, and her own short stories were long-listed for an important literary prize.

Though the episodic style of the book needs some adjusting to, the narrative quickly develops and the last third of it is very powerful indeed, and very moving in its realisation of the mind and beliefs of Michael Scot himself. She deals adroitly with his reputation as a ‘necromancer’ in some vivid scenes which reveal the power of his innate personality and mind over other people.

Cultures

This is a book which anyone interested in the development of Europe will want to read, for its sensitive delineations of a variety of cultures from the cold hills of the Scottish Borders, where Michael was born, to the hard brilliant light of Southern Spain under Muslim rule.

Michael is a man at odds with his age. Sent to Spain to make translations relating to Aristotle he fined himself affected by what he sees, feels and learns. There is a moment, for instance, when he first enters a mosque. He is overcome by a realisation of an idea of God as spirit pervading the universe.

But these translations at this date are deemed dangerous, and are suppressed. The irony of this book, and indeed of history, is that very soon after the teachings of Aristotle became not just acceptable to theologians, but essential, forming the core of St Thomas’s hyper-influential work and writing.

Michael Scot is exposed not only to Islam, but also to Judaism, and his friendships in the other culture of Europe also run through the book. Here again the fiction casts its own special light into a dark corner of Europe’s history.

The books moves towards the close with the scholars own mind beginning to absorb him. An attempt is actually made to kill him by clerical rivals. Yet having gained the regard of the Emperor when that ruler was a boy, he finds the Emperor still stands by him. Their relationship is central to the whole narrative.

He is overcome by a realisation of an idea of God as spirit pervading the universe”

Michael dies, and all the threads of the story are tied up and his life and experience rounded out finally for the reader.

This is a book filled with interest. It is very thought provoking, though some of the thoughts relate to how the bureaucratic mind in charge of religious affairs seems to remain paralysing over the centuries.

This I suspect is the kind of novel which will not come to rival say those of Hilary mantel. But even if its sales are smaller, those who read will long keep it in mind.

For explorers of the Middle Ages, in all their different aspects, this is an excellent book, a novel of ideas rather than artificially worked local colour.

Here one suspects is something very close to the truth, and the truth is always interesting, and often astonishing.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello A Matter of Interpretation by Elizabeth MacDonald

Photo: The Gloss

A Matter of Interpretation by Elizabeth MacDonald

Photo: The Gloss